A tree may be our primary connection with the universe -- but it will take us all our lives to acknowledge it

|

| The Ficus virens that outgrew the shrine |

Shashwat: Haven’t the Americans built big cities, warships, fighter jets and so on?

Me: I guess so.

Shashwat And the Germans have made very fine automobiles and autobahns?

Me: Yes, they have.

Shashwat: The French have the TGV!

Me: Yes, so?

Shashwat: So, in India, did we spend all our time celebrating festivals and meditating?

Me: Silence

|

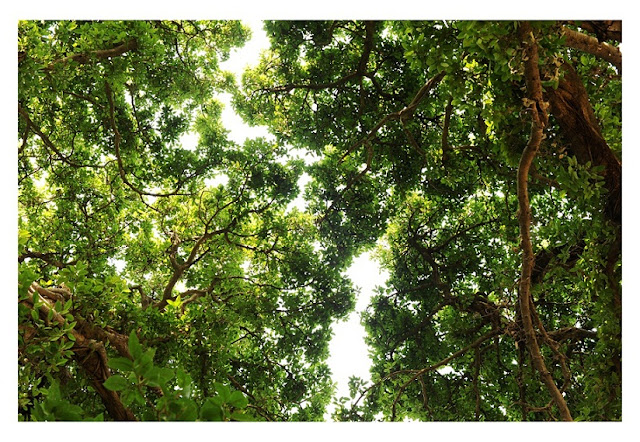

| The canopy, loved by both peacocks and Hanuman langurs |

Five minutes later the hush still rules as fervent devotees accompany the lord through the city, drumbeats announcing the procession a kilometre away from where a Sunday morning chat is languishing for lack of words. Blame it on Discovery Channel.

The best I could do was distract him with a tale.

Back in my great-great-grandmother’s time, a young boy had the duty of striking the hour. One fateful day he may have dawdled after his morning smoke or perhaps gazed at a damsel too long - and missed striking an hour. This is where things get curious, for while he missed it, the hour was still struck. His inquiries failed to find the person who had struck the hour in his absence. The lad, true to instinct, concluded that it was none other than Lord Hanuman, whom he worshipped, who had done it on his behalf. Grateful to the Lord but mindful of the fact that he had inconvenienced Him, he gave up the job. He built a shrine, planted a Ficus sapling (Ficus virens) in front of it, and announced to all and sundry that from that day on, he will perform only the Lord’s duty. He had enough of l’affaires du monde.

|

| Once I saw a cobra make its way through the network of aerial roots |

Almost 150 years on my father has inherited the piece of land on which the tree stands. I discovered its charms early in life and, when I learned that my favorite pickle was made from its spring leaf-buds, our bond deepened considerably. Summer yielded an enchanting and often forbidden lesson of natural history. Lifting up the platform bricks revealed small snakes curled up below, making me wonder if they had grew up in that position. Young Hanuman langurs (Semnopithecus entellus) socialized under the watchful eyes of the matriarch. The monsoon invigorated grass, which on closer inspection revealed clutches of peacock eggs which I dutifully counted. I apprehensively spied a cobra make its way along the sinewy branches possibly preying on treepie nests. I watched squirrels chase each other in hormone-fuelled sprints, while my dog could only gaze longingly and salivate. Inconvenienced by the water I poured, mad-with-rage scorpions emerged from their narrow slit burrows straight to my waiting collection jar. Their rage, I imagined briefly, turned into puzzlement and then helplessness. The scorpions I was forced to part with -- my grandma would have none of my entreaties to their being a part of my collection for the purpose of scientific research into scorpion sting antidote. I am sure her hand in their release was not due to any sympathy she may have felt at their cruel confinement.

|

| Peacocks lay their eggs in the wild growth beneath the tree after the first monsoon showers |

|

| The tree's local name is Pakadiya or Pakad. It is also known as Pilkhan in the north |

Grandmothers are deceptively clever.

|

| A feather, a question |

The "wooden monkey" is a gift from two years ago and the Kukri snake (Oligodon arnensis), having been mistaken for a juvenile Russell’s Viper, was killed last year - I was too late to save it.

|

| A dying Kukri snake, a victim of mistaken identity |

|

| The "Wooden Monkey" |

|

| Weaver ants have established a huge colony on the tree |

|

| The tree is nearly 150 years old and for me it's been there for ever |