Distances in the Himalaya can be tricky, especially when pointed out desultorily by a guide deprived of his liquor. Thus captained, we descended the bleak slopes of Bedni toward the village of Wan. Jennifer Nandi's spellbinding Bedni Bugyal travelogue continues...

|

| The descent from Bedni Bugyal |

With our faces turned towards the new day’s maiden blush of pink, we silently bid farewell to our mountain hosts. Then we assemble for a group photograph with an imposing Trishul as a backdrop. Our faces, now bathed in daylight still driving out the dawning sky, are focused on Sahastra. We collect our rations of energy bars from him and listen politely as he tells us yet another fable – that the village of Wan is downhill until we reach a “bump” and then it’s all downhill and gradual again! What he perversely fails to reveal is that the distance to the ‘bump’ is 8 km of rocky, steep descent and that after surmounting the said ‘bump,’ the village track is not less than 4 km to the Forest Rest House at Wan.

Sunita and I exchange knowing sidelong glances – it’s going to be a long haul.

We walk into the mist scudding over the ridge, across the frozen snarl of Himalayan roots and earth, snagging our footsteps on the charred remnants of once virile rhododendron shrubbery. Pipits and accentors lift off from our feet. We leave the bugyals behind and enter the world of laughingthrushes – a paradise for Rufous-chinned, White-throated and the Variegated. Warblers alert us with their trills. The bell-clear call of one still tantalizes us – unable as we are to identify it.

The four ponies with their caretakers rush past us, three steps to our one. We hang back leaning against soft lichen on stone to peer into an effulgence of wildness. There are Ultramarine and Rufous-gorgeted flycatchers. The undergrowth in this open weathered woodland supports thick bushes, a favoured habitat for Orange-flanked Bush Robins. Warblers abound – Western Crowned, Ashy-throated, Greenish, Large-billed, each beguiling us with its own freshness of phrase.

|

| A spot of sun brings out the diurnal drinkers but our guide is craving his moonshine |

Think of the accumulated wisdom in the millions of years of successful strategies honed for survival. We could learn a lot from a tree.

Satish is a trekker – companionable, and because of his frankness, elicits warmth. Sahastra roped him into the birding fraternity and the neophyte appears to have accepted his present circumstances with cheerful readiness. During each day’s trek he would spend time with us, alternating between Sunita and me, quizzing us on an eclectic range of subjects, in his inimical uncompetitive and reflective style. He has a fetching attitude to learning. Whatever his settled base of knowledge, his mind is not locked tight, impervious to new information. It is pure delight to introduce him to a kaleidoscopic world.

|

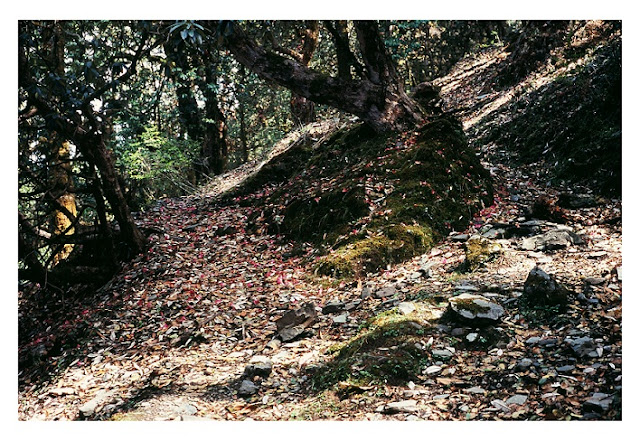

| Strewn with leaf litter, the trail to Wan |

This pine, spruce and fir forest of ineffable beauty, accompanies us all the way along the stony path that drops down to meet the Bedni, when it becomes a river of more magnanimous proportions. At the bottom of the valley the river collects enough organic particles from the mountain plants growing between the boulders near its margins to acquire just enough dissolved nutrients to support animal life. Every mountain stream has its share of Plumbeous Water Redstarts and White-capped Water Redstarts making a living at a rushing river’s edge. Both species stake out a patch of water and guard it assiduously against interlopers.

|

| The trail meanders towards the enigmatic "bump" |

|

| A Himalayan Griffon waits for the air to warm |

At the bottom of this narrow valley it has warmed sufficiently for us to jettison surplus jackets. Variations in temperature and rainfall are responsible for different ecosystems and we are welcomed by a willowy tunnel of cool shade granted gratis by riverside habitat that now includes Himalayan alder trees and Prunus cornuta. The latter is a medium-sized deciduous tree of the Rose family. Its drooping many-flowered clusters would soon become dark purple-black fruit, at first globular, but often becoming long and horn-like due to infection by insects, hence the plant’s name. But if you look closely, even the flower-clusters have assumed, in preparation perhaps, the shape of a horn.

|

| Children immerse the idol of a deity in a stream |

Sunita and I throw ourselves down on the inviting grass of the river bank scaring the Indian Tortoiseshell butterflies into sudden flight. We are tired. The stomach muscles have been working overtime to lift the weight off those stiff knees. But we are sufficiently soothed by flowering trees, birdsong, and the distinct velvet brown scent of river-bank vegetation to accept, with alacrity from Satish, the inevitable ration of ‘sattu’. However, there is an upsurge in our fortunes. He hands us each a slab of chocolate! We drink copious quantities of Electral to replenish our lost electrolytes. Devidutt throws a veil of cigarette smoke around his ration of goodies, strikes his characteristic pose and assumes an attitude of enervation. The men wash and bathe. We watch enviously as they linger in the sun-warmed water. When their clothes have baked dry, we cross the river with the right measure of reverence as one would with an animal frame of mind, mindful of black-lichened rock that could be treacherous.

|

| A male Plumbeous Water Redstart flirts his tail in a forest stream |

At last we begin the climbing of Sahastra’s ’bump’! It begins as a hillside of ruthless depredation – open oak and rhododendron severely lopped. The hillside is hushed but for the jays that shriek their dissonance in the quiet spot. Higher up we encounter tits including the Yellow-browed, easily mistakable for a warbler but for its peaked crown. The rugged hill road flattens out across scrubland and the terraced sides of the mountains bear an emerald green. Paddy is being cultivated but 1400 years ago this was not the case as attested by the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, Hiuen Tsang. The pilgrim had visited Garhwal in AD 634 and had described the soil as fertile and favourable to the growth of a poor kind of barley. The Garhwalis, whom he described as ‘a cheerful people, patient of fatigue,’ reared large numbers of sheep and ponies. However, since that time, the unfortunate Garhwalis have had to suffer tyrannical treatment at the hands of the invading Nepalese. From the 18th century onwards, small parties of Gorkhalis from Nepal had periodically plundered the border areas. Many thousand Garhwalis were sold as slaves during the Gorkhali occupation who ruled with a rod of iron. However, there is little sign of ruined agriculture and the lamentable decay that the Garhwali villages must have endured.

Photos by Sahastrarashmi, Sandeep Somasekharan and Bijoy Venugopal

Next: A night in Wan

Previously in "Odyssey to Bedni Bugyal"